Plastic is Banned, What Now? Exploring Sustainable Alternatives to Single-Use Plastic

By Hyldeguard Lee and Meike Sauerwein

On April 22, 2024, Hong Kong will take a significant stride towards environmental sustainability by implementing the first phase of the Regulation on Disposable Plastic Products, which will prohibit the sale and provision of 9 types of disposable plastic tableware that are small and difficult to recycle (including expanded polystyrene (EPS) tableware, straws, stirrers, cutlery, cups, and food containers) and other common products (e.g. cotton buds, umbrella bags, and hotel toiletries). This proactive measure aims to address the detrimental impact of single-use plastic on our environment and encourage individuals and businesses to embrace more sustainable alternatives.

Single-use plastic items have become ubiquitous in our daily lives; however, their convenience comes at a great environmental cost, especially if it leaks into the environment as we can see along Hong Kong’s coastlines. Compounding the issue, the recycling rate of plastic in Hong Kong is alarmingly low. In 2021, only 5.7% of all recycled plastics were recovered1, highlighting the need for urgent action to address the plastic waste crisis and transition towards more sustainable alternatives. - But what are sustainable alternatives?

While industries are actively exploring biodegradable materials, such as polylactic acid (PLA), or bagasse (fibrous material from sugarcane stalks) as potential solutions, it's crucial to examine whether these alternatives are truly more environmentally friendly. Surely, biodegradable materials can break down faster and reduce the risk of permanently contaminating of the environment with plastic waste. However, biodegradable materials (like PLA or paper) on Hong Kong’s landfills release compared to plastic significant amounts of greenhouse gases during degradation.2,3 So does a switch from one single-use material to another just shift the problem from one environmental category to another?

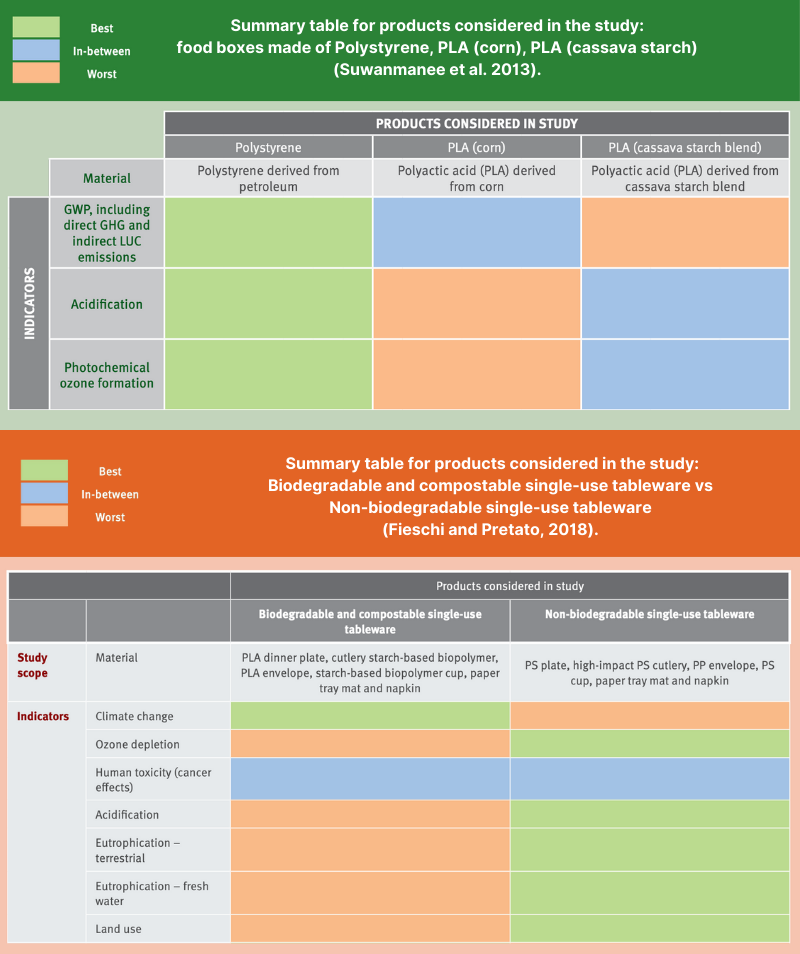

Figure 1. Qualitative comparison of Life Cycle Assessment results:

Upper: Food boxes made of Polystyrene, PLA (corn), PLA (cassava starch) (based on LCA results of Suwanmanee et al. 2013), Source: Life Cycle Initiative 2020 4;

Lower: Biodegradable and compostable vs non-biodegradable plastic-based single-use tableware (based on LCA results of Fieschi and Pretato, 2018), Source: Life Cycle Initiative 2021 (modified) 5

A meta-analysis conducted by the Life Cycle Initiative in 2020 provides a qualitative summary of various life cycle assessment reports of packaging materials, and the results of those life cycle assessment results (LCA) seem disappointing.4 For example, bio-based plastics made from natural materials such as cassava and corn, performed worse than fossil-based plastics across various environmental impact categories (refer to fig. 1). Why is that? One of the contributors is the agricultural phase which requires significant amounts of land, water or chemical inputs (e.g. pesticides, fertilizers) and thus releases emissions to soil, water and air.6

The manufacturing stage and product weight also plays a role. Take lunch boxes made from bagasse as an example: while little impacts may be allocated to the agricultural process as it often is a waste-product, the bagasse pulp bleaching process and wastewater release after pulp washing cause significant impacts across multiple areas such as climate, human and eco-toxicity. And although the oil extraction and production of PS foam boxes involve a large number of chemical and physical processes as well, the fact that bagasse is heavier and thus requires more materials can lead to its total emissions becoming higher.7 While we acknowledge that production and assessment methodologies can differ from case to case, it is hard (or rather) impossible to determine a sustainable single-use alternative.

Does that mean we should switch back to plastics? Certainly not. Yet, considering these findings, it becomes clear that while plastic is problematic, plastic alternatives do not come without environmental impacts either. If plastic alternatives do not provide the sustainable solution we seek, then shouldn’t we rather question the necessity of single-use items altogether and whether they can’t be avoided? One critical factor to consider is the willingness of Hong Kongers to embrace alternatives, such as bringing their own cups and containers.

Reusable alternatives, such as steel cutlery, aluminium water bottles or even reusable plastic containers have been studied and can be favorable in terms of their environmental performance throughout their life cycles.8,9 For citizens who do not remember (or are not willing to) bring their own container, exploring the potential of a reusable container borrowing and returning system presents an intriguing solution where customers can borrow containers or cups and return them to designated spots for drop-off.9 Although reusable containers also need to be manufactured (and cause impacts), using them repeatedly brings down these impacts per use. In contrast to single-use items, increasing reuse rates of such containers, adopting reasonable washing practices, and optimizing the design of reuse-rental systems allows us to optimize "bring your own" or “rental container systems” from an environmental point of view and make them the most sustainable option if take-away can’t be avoided.

The ban on single-use plastic items in Hong Kong marks a pivotal moment in the fight against plastic pollution and environmental degradation. While it is unrealistic to expect a complete elimination of plastic from our lives, it is crucial to recognize that pushing for alternative single-use materials alone is not the ultimate solution and will create new environmental issues. Instead, the key lies in fostering awareness on where plastic and packaging can be entirely avoided and where reusable products are an option, while striving to minimize the usage of single-use plastic-alternatives.

The opinions expressed within the writeup are solely the author's and do not reflect the opinions of the HKUST Life Cycle Lab.

Reference:

1 Monitoring of Solid Waste in Hong Kong – Waste Statistics for 2021, Environmental Protection Department.

2 Troy A. Hottle, Melissa M. Bilec, Amy E. Landis (2017). Biopolymer production and end of life comparisons using life cycle assessment. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 122, Pages 295-306. ISSN 0921-3449, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.03.002.

3 Demetrious, A., Crossin, E (2019). Life cycle assessment of paper and plastic packaging waste in landfill, incineration, and gasification-pyrolysis. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 21, 850–860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-019-00842-4